Sourcescrub and Grata are joining forces to deliver the market’s most complete market intelligence platform

Learn more

We see it in the news all the time: a company is acquired by another, or two companies merge together. Or, they "go public" (i.e., listed on the public stock markets and owned by anyone who holds shares) or get bought and re-privatized (i.e., someone — usually a private equity firm — buys all the shares and delists the company from the public market).

There are countless ways for company ownership to change hands and capital to be transferred, but one of the most popular ways this happens is through private equity (PE) funds. Let’s take a deep dive with us into how private equity funds are structured, including the typical people and entities involved, how everyone involved in the fund makes money, and more.

The simplest definition of a private equity fund is that it's an instrument for allowing multiple investors (called Limited Partners, or LPs) to pool their money together and buy ownership stakes in multiple operating companies. This pooled money is the private equity fund, which is then managed by a General Partner (GP), also known as a fund manager. Of course, the goal of this PE fund is to return a profit on the investments made by the LPs.

When you dig into the details, however, there are many different specifics that impact how the PE fund functions and interacts with the players involved, including how and by whom the money is managed, the separate legal entities involved, and how each of the entities makes money.

Don't worry — we'll unravel each of these layers for how private equity funds are structured and function in later sections.

When talking about private equity structure, it's important to understand that there are many different types of fund structures. Two of the more popular types are venture capital (VC) funds and fund-of-funds, though there are many more, including hedge funds.

These different fund structures exist to support different types of investment. For example, venture capitalists generally invest their capital into early-stage startups, taking on much higher risk than other investments in the hopes of seeing much higher returns. They generally do not purchase a company outright, as in the case of acquisitions, and instead secure a minority stake (under 50%) of the business.

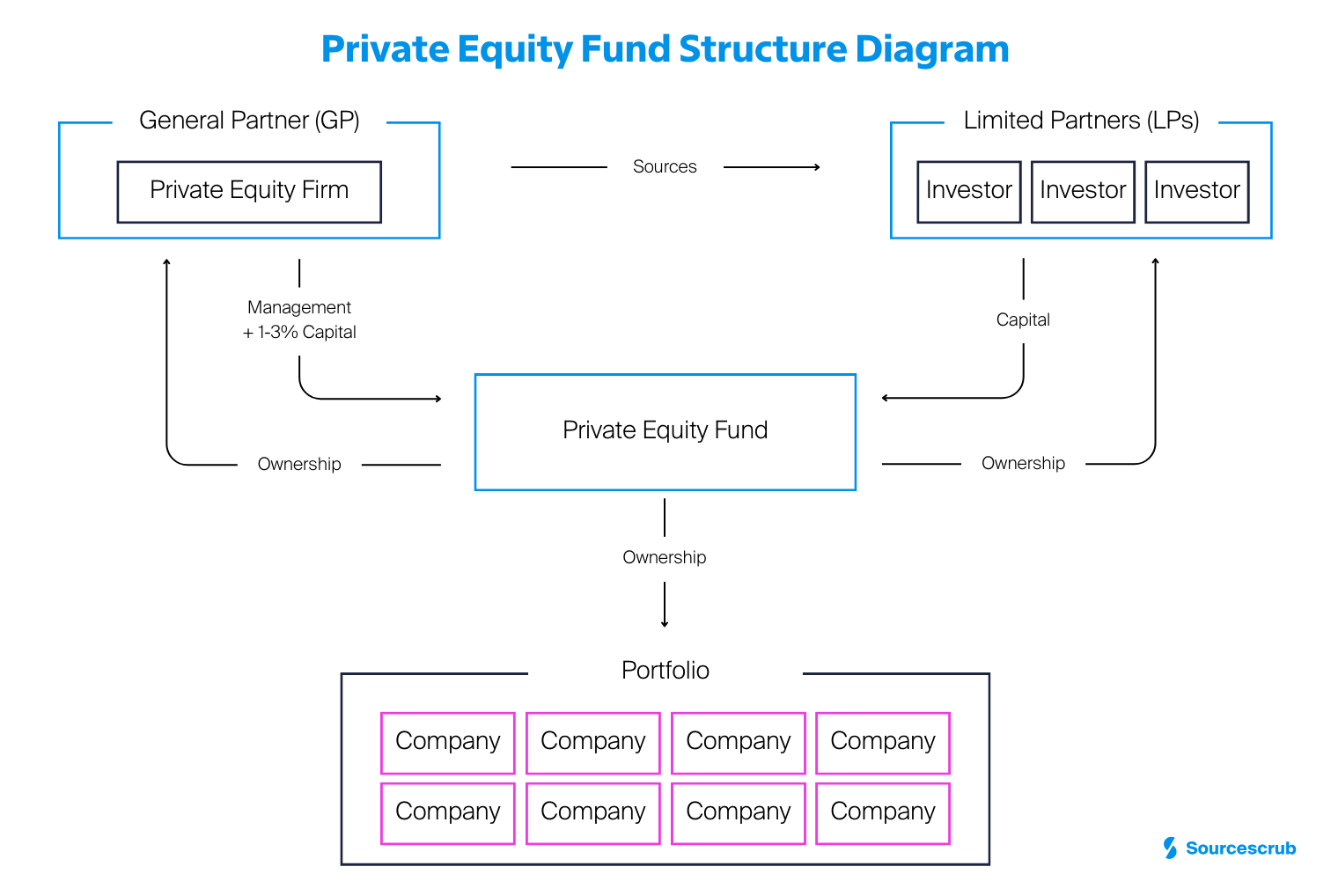

There are three specific players in a private equity fund: the General Partner, Limited Partners, and the fund itself. Each of these players is a separate entity, legally, to reduce liability and provide clear ownership lines of assets. Here is a private equity fund structure diagram to help visualize the relationships:

To best understand how private equity funds are structured, it's important to start at the source: the General Partner.

To ensure a private equity fund runs properly, it must have the right team to manage it. For PE funds, it all begins with the General Partner, AKA the private equity firm. The GP has legal authority over the fund, sources the LPs who supply the capital, and makes the decisions about how to use that capital, including what operating companies are in the investment portfolio.

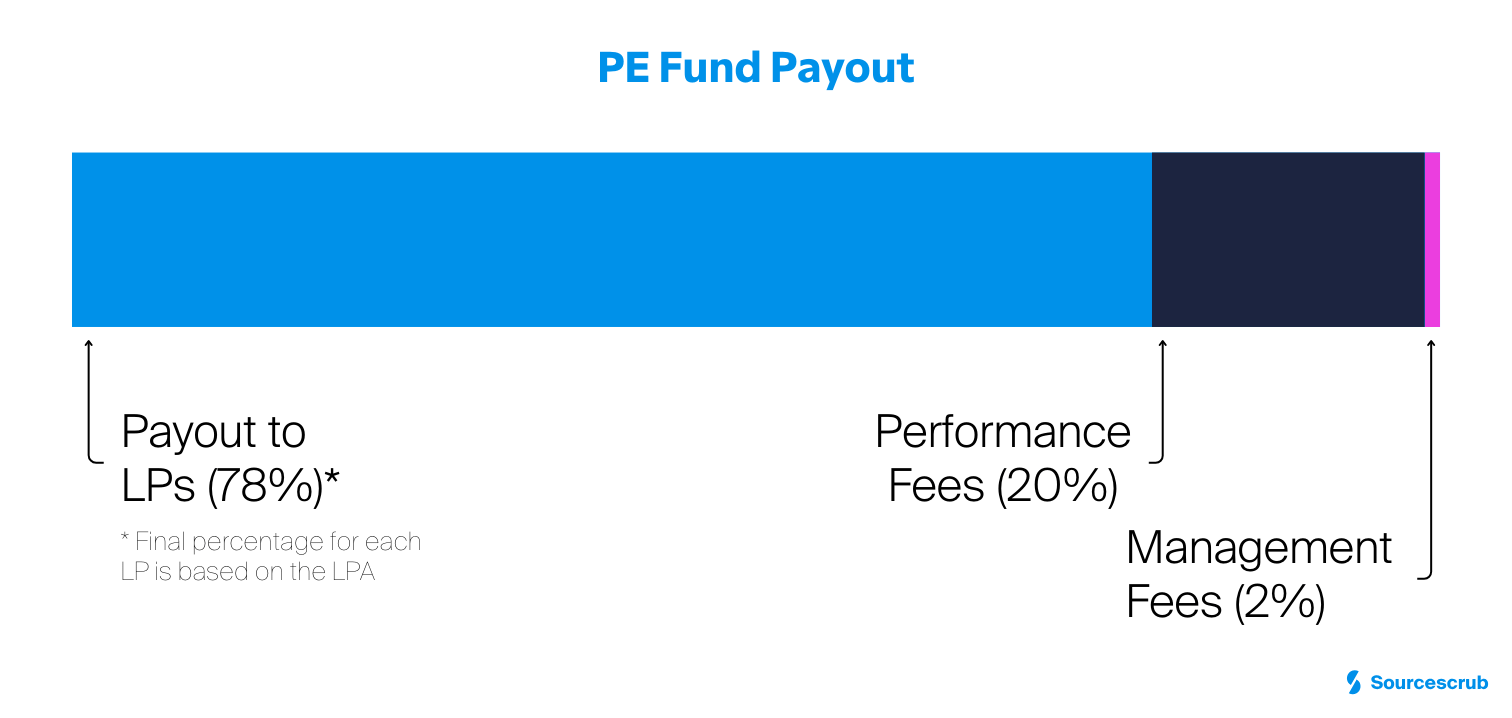

As such, the GP is also known as the fund manager. They make money based on two types of fees: management and performance fees. Management fees, which are charged regardless of whether the fund turns a profit, are generally around 2% of the total assets under management (AUM). Performance fees, which are only paid if the fund is profitable, can vary based on the agreement between the GP and the LPs, but are usually 20% of the gross profit.

Often, fund managers will put a small portion of the capital themselves — typically 1-3% of the overall fund size — to have "skin in the game." This helps the LPs feel a bit more secure that the firm is making decisions in the fund's best interest, as well as gives the GPs partial ownership of the fund because they invested their own capital.

Since the General Partner in a private equity fund is the PE firm itself, it's important to understand how private equity firms are structured. Within a firm, there are a few different levels of employees, all working to ensure the success (AKA profitability) of their funds.

The foundation of any good private equity firm is the data it uses and the analysts and associates that analyze it. From sourcing investment opportunities and mapping markets to understanding current events and forecasting future trends, the analysts and associates help the more senior members, such as VPs and Principals, make their decisions based on data.

VPs are usually responsible for deciding which individual investments to pursue, while Principals generally manage entire portfolios of companies, including entire funds. Both VPs and Principals are the faces of their respective deals, serving as the closers.

At the top of the firm are the Partners and Managing Partners, who oversee the entire firm. They are responsible for guiding the firm and choosing its overall path forward, as well as helping to source LPs and secure capital for the firm's funds. This private equity structure ensures all the key players are in place for the firm's and its funds’ overall success.

As we discussed earlier, LPs are the people who supply the fund with the capital necessary to invest in the fund's portfolio. LPs get returns on their investments when the fund is liquidated. Examples of liquidation events are mergers, acquisitions, or initial public offerings (IPOs).

As long as the liquidation event is profitable, the LPs get their investment back as well as a percentage of the profit. This percentage differs based on what was agreed upon in the Limited Partnership Agreements (LPAs), which we'll discuss in a later section. If the fund is not profitable, LPs only lose what they invested. Any difference between the value of the fund upon liquidation and what was invested is the responsibility of the GP.

Because of the inherent risk, LPs are not your typical retail investor like those with shares in public companies (e.g., using money contributed to retirement accounts). Very few investors actually qualify to become an LP, or what's known as an accredited investor. Accredited investors must have:

Because of these requirements, most LPs are institutional investors (e.g., endowments, family offices, etc.) or very high net-worth individuals.

Finally, there's the fund itself. Private equity funds are their own separate legal entity, usually for both liability and tax reasons, and are often founded as a Limited Liability Company (LLC) or a Limited Partnership (LP). The reason for this is both LLCs and Limited Partnerships are "pass-through businesses" and not subject to corporate taxes.

The tax liability, instead, is passed through directly to those that gave capital to the fund: the GP and LPs. Having the fund as a legally separate entity also enables the GP to manage and have authority over what the fund does, per the Limited Partnership Agreement. Plus, this way, the fund can also legally own the shares of the companies purchased by the fund's capital.

Limited Partnership Agreements are the conditions through which the Limited Partners provide their capital, including general fund characteristics, such as duration, term extension guidelines, fees, and payout structure. They are essentially the contracts that stipulate the investment terms, such as the roles and associated risks and liabilities for each party in the agreement, as well as how much the fund can contribute to each investment.

LPAs also determine the general direction for the fund with regard to its investment thesis, whether there will be any restrictions on which companies can be in the portfolio, and how diversified the portfolio needs to be.

When firms decide how their private equity funds are structured, they need to consider the needs of their investors, investments, and, of course, the firm itself. An important part of that process is understanding the right direction for the fund to take, which can only be done with the right support structure — i.e., the firm's tech stack — in place.

With dealmakers who harness technology and take a data-driven approach in their sourcing efforts transacting 55% more than their peers, it's clear that technology plays a key role in success. To learn the core components of the modern dealmaker's tech stack, download our guide.